Since starting the basketball team at Milwaukee Academy of Science (M.A.S.) in 2007, head coach Agape Keys has held high standards for his players on the hardwood and in the classroom. “He (Keys) wants us to practice hard and do everything hard at basketball,” Milwaukee Academy of Science sophomore and varsity basketball player Albert Harrell said. “He wants the same for school.”

At M.A.S. Keys is not only the head basketball coach, but he also works as a student-support specialist for high school students. With this role, the impact Keys has extends to all students. Early mornings and late nights also come with the extra responsibilities for Keys.

“I get here at six in the morning and don’t leave sometimes until 10 at night,” Keys said. “If I can motivate a kid to stay out (of) the streets or stay busy until he goes home and goes to sleep, that’s my motto: every day of my life for 17 years.”

The motto that Keys lives by is making sure the students who see him in the hallway or the ones he coaches from the sideline stay busy to benefit their own future. He understands the difficulties they face as a M.A.S. student.

MAS is a K4-12 school, and has a total enrollment of over 1,300 students. Within that student population, 97% of the students face financial hardships. Keys understands that he can impact his players off the court as the basketball coach. He does this by holding his players to high standards on the court and in the classroom. Wisconsin has the ninth-lowest high school graduation rate for Black students in the United States at 83%. On top of that, low income students are seven times more likely to drop out of school than students from higher income families. With Milwaukee being one of the most segregated cities in America and the odds already stacked against Black students, these challenges shape the lives of students at MAS.

In his coaching career, which began as an Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) coach, Keys has found it vital to build meaningful relationships with his players. Keys makes sure that his players are at practice on time with their shoes laced up, all while not letting them see the struggles that factor into it.

“The struggle was making sure we could get the kids [to practice] and back. But the kids never felt the struggle. We never showed the kids that it was a struggle to get them there,” Keys said.

The challenge of getting every player to practice still exists for Keys and his coaching staff, but they continue to get them in the gym and make sure they come with something in their stomach. “He’ll buy us Lyfts to practice if we don’t have a ride (and) buy us food if we don’t have the money,” Albert Harrell said.

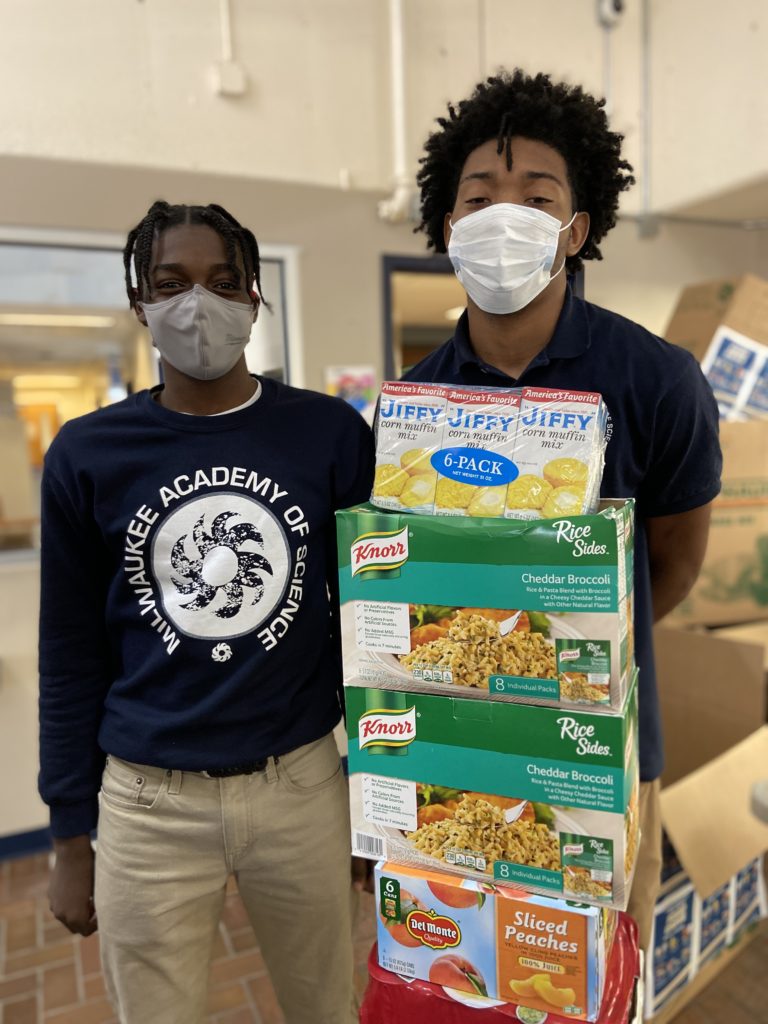

Keys does not just look out for his players and the students at M.A.S.; he also has those in need in the outside community in mind, too.

As a way to get his players involved in the community and to bring his team closer together, Keys and his players have a day of service in which they help at the local pantry. “He wants us to always support others that don’t have enough,” his son and freshman player Agape Keys Jr. said. Teaching his players and the younger generation to help those in need in their communities is something Keys wishes more people would do. “We don’t have enough of what I’m doing out in the world to mold these kids and what they need to be in life,” Keys said.

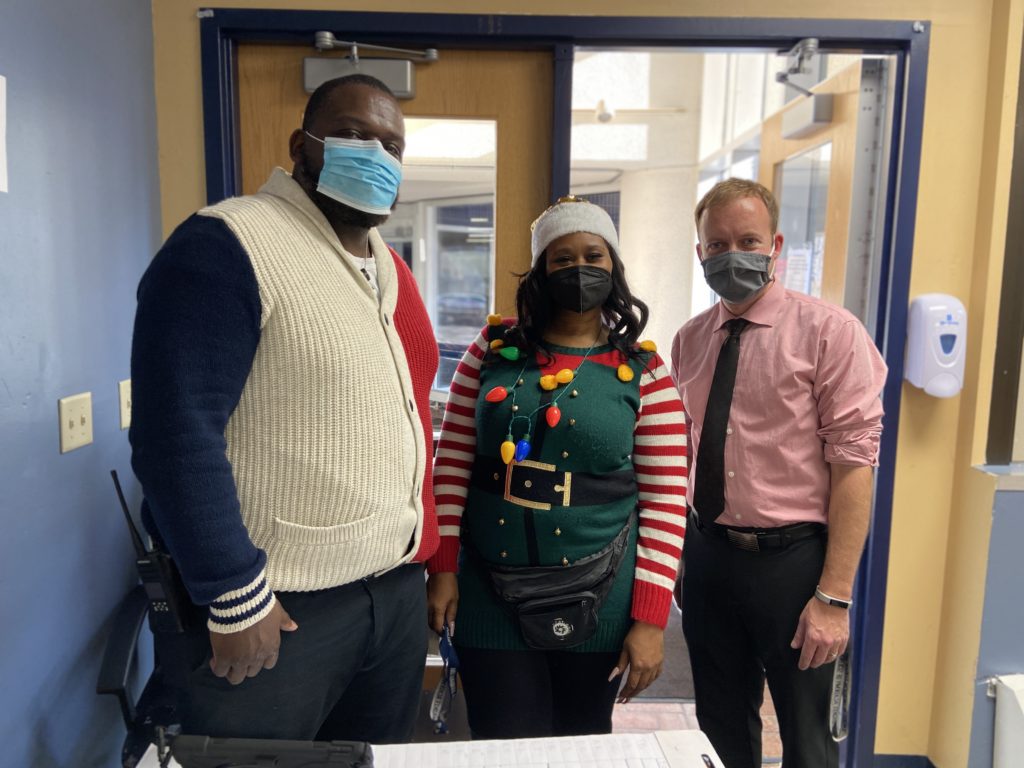

Reggie Bell, an English teacher at M.A.S, teams up with Keys to further support students. He also shares the sideline with Keys on gameday. Bell finds that the influence he and Keys can have is even greater with their extended involvement at the school during the day as well. “With both of us working in the school building, we have more impact on the kids,” Bell said. Keys understands that there are two parts to being a student-athlete and so he pushes his players to be equally committed to their academics as their game.

“We have [grade] checks every Monday. And if we get lower than a C, then we have to stay after [class] and do work with that teacher,” Keys Jr. said. There are potential consequences waiting at practice if someone on the team gets a bad grade or if someone wasn’t on their best behavior at school. Those consequences typically involve sprints for everyone on the team. “He’s all about school. If somebody’s doing something they ain’t supposed to do, all of that is just going to affect our practice. As soon as we get to the gym, go to the line, and just start running the whole practice,” Albert Harrell said.

It’s harder for the public to see how the players are doing in school, but the results on the court can and have been seen by those in Milwaukee. During the 2021-22 season Keys surpassed 200 career wins and ended the season by taking M.A.S. to State for the first time. Keys Jr. has been around the team his whole life as the coach’s son, but for M.A.S.’s first trip to State he was one of the players on the court, making it memorable for him and his dad. “It was [so special] because it’s the first time he’s made it,” to state, said Keys Jr. Keys Jr, Harrell and his teammates see what Keys is doing for them and his work doesn’t go unnoticed.

“When we need him, he’s always there. Like, there wasn’t a time that he ever missed, that he wasn’t there for us,” Albert Harrell said. “Most people don’t have coaches like that go out of their way for them. It’s a blessing.”

Full links:

97% of the students face financial hardships

Ninth-lowest

Seven times more likely to drop out of school

Milwaukee being one of the most segregated cities in America